Romeo and Juliet is a

tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about two young

star-crossed lovers whose deaths ultimately reconcile their feuding families. It was among

Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetime and, along with

Hamlet, is one of his most frequently performed plays. Today, the title characters are regarded as

archetypal young lovers.

Romeo and Juliet belongs to a tradition of tragic

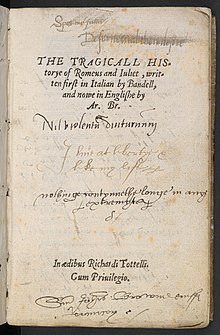

romances stretching back to antiquity. The plot is based on an Italian tale translated into verse as

The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet by

Arthur Brooke in 1562, and retold in prose in

Palace of Pleasure by

William Painter

in 1567. Shakespeare borrowed heavily from both, but expanded the plot

by developing a number of supporting characters, particularly

Mercutio and

Paris. Believed to have been written between 1591 and 1595, the play was first published in a

quarto

version in 1597. The text of the first quarto version was of poor

quality, however, and later editions corrected the text to conform more

closely with Shakespeare's original.

Shakespeare's use of his poetic

dramatic structure

(especially effects such as switching between comedy and tragedy to

heighten tension, his expansion of minor characters, and his use of

sub-plots to embellish the story) has been praised as an early sign of

his dramatic skill. The play ascribes different poetic forms to

different characters, sometimes changing the form as the character

develops. Romeo, for example, grows more adept at the

sonnet over the course of the play.

Romeo and Juliet has been adapted numerous times for stage, film, musical and opera venues. During the

English Restoration, it was revived and heavily revised by

William Davenant.

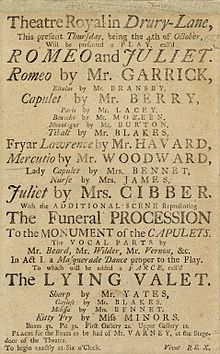

David Garrick's 18th-century version also modified several scenes, removing material then considered indecent, and

Georg Benda's

Romeo und Julie omitted much of the action, and added a happy ending. Performances in the 19th century, including

Charlotte Cushman's, restored the original text, and focused on greater

realism.

John Gielgud's

1935 version kept very close to Shakespeare's text, and used

Elizabethan costumes and staging to enhance the drama. In the 20th and

into the 21st century, the play has been adapted in versions as diverse

as

George Cukor's 1935 film

Romeo and Juliet,

Franco Zeffirelli's 1968 version

Romeo and Juliet, and

Baz Luhrmann's 1996 MTV-inspired

Romeo + Juliet.

Characters

- Ruling house of Verona

- House of Capulet

- Capulet is the patriarch of the house of Capulet.

- Lady Capulet is the matriarch of the house of Capulet.

- Juliet is the 13-year-old daughter of Capulet, and the play's female protagonist.

- Tybalt is a cousin of Juliet, and the nephew of Lady Capulet.

- The Nurse is Juliet's personal attendant and confidante.

- Rosaline is Lord Capulet's niece, and Romeo's love in the beginning of the story.

- Peter, Sampson and Gregory are servants of the Capulet household.

|

- House of Montague

- Montague is the patriarch of the house of Montague.

- Lady Montague is the matriarch of the house of Montague.

- Romeo is the son of Montague, and the play's male protagonist.

- Benvolio is Romeo's cousin and best friend.

- Abram and Balthasar are servants of the Montague household.

- Others

- Friar Laurence is a Franciscan friar, and is Romeo's confidant.

- Friar John is sent to deliver Friar Laurence's letter to Romeo.

- An Apothecary who reluctantly sells Romeo poison.

- A Chorus reads a prologue to each of the first two acts.

|

Synopsis

The play, set in

Verona,

Italy, begins with a street brawl between

Montague and

Capulet servants who, like their masters, are sworn enemies.

Prince Escalus of Verona intervenes and declares that further breach of the peace will be punishable by death. Later,

Count Paris talks to Capulet about marrying his daughter

Juliet, but Capulet asks Paris to wait another two years and invites him to attend a planned Capulet

ball. Lady Capulet and Juliet's nurse try to persuade Juliet to accept Paris's courtship.

Meanwhile,

Benvolio talks with his cousin

Romeo,

Montague's son, about Romeo's recent depression. Benvolio discovers

that it stems from unrequited infatuation for a girl named

Rosaline, one of Capulet's nieces. Persuaded by Benvolio and

Mercutio,

Romeo attends the ball at the Capulet house in hopes of meeting

Rosaline. However, Romeo instead meets and falls in love with Juliet.

Juliet's cousin,

Tybalt,

is enraged at Romeo for sneaking into the ball, but is only stopped

from killing Romeo by Juliet's father, who doesn't wish to shed blood in

his house. After the ball, in what is now called the "balcony scene",

Romeo sneaks into the Capulet orchard and overhears Juliet at her window

vowing her love to him in spite of her family's hatred of the

Montagues. Romeo makes himself known to her and they agree to be

married. With the help of

Friar Laurence, who hopes to reconcile the two families through their children's union, they are secretly married the next day.

L’ultimo bacio dato a Giulietta da Romeo by

Francesco Hayez. Oil on canvas, 1823.

Tybalt, meanwhile, still incensed that Romeo had sneaked into the

Capulet ball, challenges him to a duel. Romeo, now considering Tybalt

his kinsman, refuses to fight. Mercutio is offended by Tybalt's

insolence, as well as Romeo's "vile submission",

and accepts the duel on Romeo's behalf. Mercutio is fatally wounded

when Romeo attempts to break up the fight. Grief-stricken and wracked

with guilt, Romeo confronts and slays Tybalt.

Montague argues that Romeo has justly executed Tybalt for the murder

of Mercutio. The Prince, now having lost a kinsman in the warring

families' feud, exiles Romeo from Verona, under penalty of death if he

ever returns. Romeo secretly spends the night in Juliet's chamber, where

they

consummate

their marriage. Capulet, misinterpreting Juliet's grief, agrees to

marry her to Count Paris and threatens to disown her when she refuses to

become Paris's "joyful bride". When she then pleads for the marriage to be delayed, her mother rejects her.

Juliet visits Friar Laurence for help, and he offers her a potion

that will put her into a deathlike coma for "two and forty hours".

The Friar promises to send a messenger to inform Romeo of the plan, so

that he can rejoin her when she awakens. On the night before the

wedding, she takes the drug and, when discovered apparently dead, she is

laid in the family crypt.

The messenger, however, does not reach Romeo and, instead, Romeo

learns of Juliet's apparent death from his servant Balthasar.

Heartbroken, Romeo buys poison from an

apothecary and goes to the Capulet

crypt.

He encounters Paris who has come to mourn Juliet privately. Believing

Romeo to be a vandal, Paris confronts him and, in the ensuing battle,

Romeo kills Paris. Still believing Juliet to be dead, he drinks the

poison. Juliet then awakens and, finding Romeo dead, stabs herself with

his dagger. The feuding families and the Prince meet at the tomb to find

all three dead. Friar Laurence recounts the story of the two

"star-cross'd lovers". The families are reconciled by their children's

deaths and agree to end their violent feud. The play ends with the

Prince's elegy for the lovers: "For never was a story of more woe/Than

this of Juliet and her Romeo."

Sources

Romeo and Juliet borrows from a tradition of tragic love stories dating back to antiquity. One of these is

Pyramus and Thisbe, from

Ovid's

Metamorphoses,

which contains parallels to Shakespeare's story: the lovers' parents

despise each other, and Pyramus falsely believes his lover Thisbe is

dead. The

Ephesiaca of

Xenophon of Ephesus,

written in the 3rd century, also contains several similarities to the

play, including the separation of the lovers, and a potion that induces a

deathlike sleep.

One of the earliest references to the names

Montague and

Capulet is from

Dante's

Divine Comedy, who mentions the Montecchi (

Montagues) and the Cappelletti (

Capulets) in canto six of

Purgatorio:

Come and see, you who are negligent,

Montagues and Capulets, Monaldi and Filippeschi

One lot already grieving, the other in fear.

However, the reference is part of a polemic against the moral decay of

Florence,

Lombardy and the

Italian Peninsula as a whole;

Dante, through his characters, chastises

German King Albert I for neglecting his responsibilities towards Italy ("you who are negligent"), and successive

popes for their encroachment from purely spiritual affairs, thus leading to a climate of incessant bickering and warfare between

rival political parties in Lombardy. History records the name of the family

Montague as being lent to such a political party in

Verona, but that of the

Capulets as from a

Cremonese family, both of whom play out their conflict in

Lombardy as a whole rather than within the confines of

Verona.

Allied to rival political factions, the parties are grieving ("One lot

already grieving") because their endless warfare has led to the

destruction of both parties,

rather than a grief from the loss of their ill-fated offspring as the

play sets forth, which appears to be a solely poetic creation within

this context.

The earliest known version of the

Romeo and Juliet tale akin to Shakespeare's play is the story of

Mariotto and Gianozza by

Masuccio Salernitano, in the 33rd novel of his

Il Novellino published in 1476. Salernitano sets the story in

Siena

and insists its events took place in his own lifetime. His version of

the story includes the secret marriage, the colluding friar, the fray

where a prominent citizen is killed, Mariotto's exile, Gianozza's forced

marriage, the potion plot, and the crucial message that goes astray. In

this version, Mariotto is caught and beheaded and Gianozza dies of

grief.

Modern form

Luigi da Porto (1485–1529) adapted the story as

Giulietta e Romeo and included it in his

Historia novellamente ritrovata di due Nobili Amanti, written in 1524 and published posthumously in 1531 in Venice. Da Porto drew on

Pyramus and Thisbe,

Boccacio's

Decameron, and Salernitano's

Mariotto e Ganozza,

but it is likely that his story is also autobiographical: present as a

soldier at a ball on 26 February 1511 at a residence of the Savorgnan

clan in

Udine,

following a peace ceremony with the opposite Strumieri, Da Porta fell

in love with Lucina, the daughter of the house, but relationships of

their mentors prevented advances. The next morning,

the Savorgnans led an attack on the city, and many members of the Strumieri were murdered. When years later, half-paralyzed from a battle-wound, he wrote

Giulietta e Romeo in

Montorso Vicentino (from where he could see the "castles" of

Verona), he dedicated the

novella to

bellisima e leggiadra madonna Lucina Savorgnan.

Da Porto presented his tale as historically true and claimed it took

place a century earlier than Salernitano had it, in the days Verona was

ruled by

Bartolomeo II della Scala (anglicized as

Prince Escalus).

Da Porto gave Romeo and Juliet most of its modern form, including the

names of the lovers, the rival families of Montecchi and Capuleti, and

the location in Verona. He named the friar

Laurence (

frate Lorenzo) and introduced the characters

Mercutio (

Marcuccio Guertio),

Tybalt (

Tebaldo Cappelleti),

Count Paris (

conti (Paride) di Lodrone), the faithful servant, and

Giulietta's nurse.

Da Porto originated the remaining basic elements of the story: the

feuding families, Romeo -left by his mistress- meeting Giulietta at a

dance at her house, the love scenes (including the balcony scene), the

periods of despair, Romeo killing Giulietta's cousin (Tebaldo), and the

families' reconciliation after the lovers' suicides. In da Porto's version Romeo takes poison and Giulietta stabs herself with his dagger.

In 1554,

Matteo Bandello published the second volume of his

Novelle, which included his version of

Giuletta e Romeo,

probably written between 1531 and 1545. Bandello lengthened and weighed

down the plot, while leaving the storyline basically unchanged (though

he did introduce

Benvolio). Bandello's story was translated into French by

Pierre Boaistuau in 1559 in the first volume of his

Histories Tragiques. Boaistuau adds much moralising and sentiment, and the characters indulge in rhetorical outbursts.

In his 1562

narrative poem The Tragical History of Romeus and Juliet, Arthur Brooke translated Boaistuau faithfully, but adjusted it to reflect parts of Chaucer's

Troilus and Criseyde. There was a trend among writers and playwrights to publish works based on Italian

novelles—Italian tales were very popular among theatre-goers—and Shakespeare may well have been familiar with

William Painter's 1567 collection of Italian tales titled

Palace of Pleasure. This collection included a version in prose of the

Romeo and Juliet story named

"The goodly History of the true and constant love of Romeo and Juliett". Shakespeare took advantage of this popularity:

The Merchant of Venice,

Much Ado About Nothing,

All's Well That Ends Well,

Measure for Measure, and

Romeo and Juliet are all from Italian

novelle.

Romeo and Juliet

is a dramatisation of Brooke's translation, and Shakespeare follows the

poem closely, but adds extra detail to both major and minor characters

(in particular the Nurse and Mercutio).

Christopher Marlowe's

Hero and Leander and

Dido, Queen of Carthage,

both similar stories written in Shakespeare's day, are thought to be

less of a direct influence, although they may have helped create an

atmosphere in which tragic love stories could thrive.

Date and text

Title page of the first edition

It is unknown when exactly Shakespeare wrote

Romeo and Juliet. Juliet's nurse refers to an earthquake she says occurred 11 years ago. This may refer to the

Dover Straits earthquake of 1580,

which would date that particular line to 1591. Other earthquakes—both

in England and in Verona—have been proposed in support of the different

dates. But the play's stylistic similarities with

A Midsummer Night's Dream and other plays conventionally dated around 1594–95, place its composition sometime between 1591 and 1595. One conjecture is that Shakespeare may have begun a draft in 1591, which he completed in 1595.

Shakespeare's

Romeo and Juliet was published in two

quarto editions prior to the publication of the

First Folio

of 1623. These are referred to as Q1 and Q2. The first printed edition,

Q1, appeared in early 1597, printed by John Danter. Because its text

contains numerous differences from the later editions, it is labelled a '

bad quarto';

the 20th-century editor T. J. B. Spencer described it as "a detestable

text, probably a reconstruction of the play from the imperfect memories

of one or two of the actors", suggesting that it had been pirated for

publication.

An alternative explanation for Q1's shortcomings is that the play (like

many others of the time) may have been heavily edited before

performance by the playing company. In any event, its appearance in early 1597 makes 1596 the latest possible date for the play's composition.

The superior Q2 called the play

The Most Excellent and Lamentable Tragedie of Romeo and Juliet. It was printed in 1599 by

Thomas Creede and published by

Cuthbert Burby. Q2 is about 800 lines longer than Q1.

Its title page describes it as "Newly corrected, augmented and

amended". Scholars believe that Q2 was based on Shakespeare's

pre-performance draft (called his

foul papers),

since there are textual oddities such as variable tags for characters

and "false starts" for speeches that were presumably struck through by

the author but erroneously preserved by the typesetter. It is a much

more complete and reliable text, and was reprinted in 1609 (Q3), 1622

(Q4) and 1637 (Q5). In effect, all later Quartos and Folios of

Romeo and Juliet

are based on Q2, as are all modern editions since editors believe that

any deviations from Q2 in the later editions (whether good or bad) are

likely to arise from editors or compositors, not from Shakespeare.

The First Folio text of 1623 was based primarily on Q3, with

clarifications and corrections possibly coming from a theatrical

promptbook or Q1. Other Folio editions of the play were printed in 1632 (F2), 1664 (F3), and 1685 (F4). Modern versions—that take into account several of the Folios and Quartos—first appeared with

Nicholas Rowe's 1709 edition, followed by

Alexander Pope's

1723 version. Pope began a tradition of editing the play to add

information such as stage directions missing in Q2 by locating them in

Q1. This tradition continued late into the

Romantic period. Fully annotated editions first appeared in the

Victorian period

and continue to be produced today, printing the text of the play with

footnotes describing the sources and culture behind the play.

Themes and motifs

Scholars have found it extremely difficult to assign one specific, overarching

theme

to the play. Proposals for a main theme include a discovery by the

characters that human beings are neither wholly good nor wholly evil,

but instead are more or less alike,

awaking out of a dream and into reality, the danger of hasty action, or

the power of tragic fate. None of these have widespread support.

However, even if an overall theme cannot be found it is clear that the

play is full of several small, thematic elements that intertwine in

complex ways. Several of those most often debated by scholars are

discussed below.

Love

"Romeo

If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle sin is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

Juliet

Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands that pilgrims' hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmers' kiss."

—Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene V

Romeo and Juliet is sometimes considered to have no unifying theme, save that of young love.

Romeo and Juliet have become emblematic of young lovers and doomed

love. Since it is such an obvious subject of the play, several scholars

have explored the language and historical context behind the romance of

the play.

On their first meeting, Romeo and Juliet use a form of communication

recommended by many etiquette authors in Shakespeare's day: metaphor. By

using metaphors of saints and sins, Romeo was able to test Juliet's

feelings for him in a non-threatening way. This method was recommended

by

Baldassare Castiglione

(whose works had been translated into English by this time). He pointed

out that if a man used a metaphor as an invitation, the woman could

pretend she did not understand him, and he could retreat without losing

honour. Juliet, however, participates in the metaphor and expands on it.

The religious metaphors of "shrine", "pilgrim" and "saint" were

fashionable in the poetry of the time and more likely to be understood

as romantic rather than blasphemous, as the concept of sainthood was

associated with the Catholicism of an earlier age.

Later in the play, Shakespeare removes the more daring allusions to

Christ's resurrection in the tomb he found in his source work: Brooke's

Romeus and Juliet.

In the later balcony scene, Shakespeare has Romeo overhear Juliet's

soliloquy, but in Brooke's version of the story her declaration is done

alone. By bringing Romeo into the scene to eavesdrop, Shakespeare breaks

from the normal sequence of courtship. Usually a woman was required to

be modest and shy to make sure that her suitor was sincere, but breaking

this rule serves to speed along the plot. The lovers are able to skip

courting, and move on to plain talk about their relationship— agreeing

to be married after knowing each other for only one night.

In the final suicide scene, there is a contradiction in the message—in

the Catholic religion, suicides were often thought to be condemned to

hell, whereas people who die to be with their loves under the "

Religion of Love"

are joined with their loves in paradise. Romeo and Juliet's love seems

to be expressing the "Religion of Love" view rather than the Catholic

view. Another point is that although their love is passionate, it is

only consummated in marriage, which keeps them from losing the

audience's sympathy.

The play arguably equates love and sex with death. Throughout the

story, both Romeo and Juliet, along with the other characters, fantasise

about

it as a dark being, often equating it with a lover. Capulet, for example, when he first discovers Juliet's (faked) death, describes it as having

deflowered his daughter.

Juliet later erotically compares Romeo and death. Right before her

suicide she grabs Romeo's dagger, saying "O happy dagger! This is thy

sheath. There rust, and let me die."

Fate and chance

"O, I am fortune's fool!"

—Romeo, Act III Scene I

Scholars are divided on the role of fate in the play. No consensus

exists on whether the characters are truly fated to die together or

whether the events take place by a series of unlucky chances. Arguments

in favour of fate often refer to the description of the lovers as "

star-cross'd". This phrase seems to hint that the stars have predetermined the lovers' future.

John W. Draper points out the parallels between the Elizabethan belief in

the four humours

and the main characters of the play (for example, Tybalt as a

choleric). Interpreting the text in the light of humours reduces the

amount of plot attributed to chance by modern audiences.

Still, other scholars see the play as a series of unlucky chances—many

to such a degree that they do not see it as a tragedy at all, but an

emotional

melodrama. Ruth Nevo believes the high degree to which chance is stressed in the narrative makes

Romeo and Juliet

a "lesser tragedy" of happenstance, not of character. For example,

Romeo's challenging Tybalt is not impulsive; it is, after Mercutio's

death, the expected action to take. In this scene, Nevo reads Romeo as

being aware of the dangers of flouting

social norms, identity and commitments. He makes the choice to kill, not because of a

tragic flaw, but because of circumstance.

Duality (light and dark)

"O brawling love, O loving hate,

O any thing of nothing first create!

O heavy lightness, serious vanity,

Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms,

Feather of lead, bright smoke, cold fire, sick health,

Still-waking sleep, that is not what it is!"

—Romeo, Act I Scene I

Scholars have long noted Shakespeare's widespread use of light and dark

imagery throughout the play.

Caroline Spurgeon

considers the theme of light as "symbolic of the natural beauty of

young love" and later critics have expanded on this interpretation. For example, both Romeo and Juliet see the other as light in a

surrounding darkness. Romeo describes Juliet as being like the sun, brighter than a torch, a jewel sparkling in the night, and a bright angel among dark clouds. Even when she lies apparently dead in the tomb, he says her "beauty makes This vault a feasting presence full of light." Juliet describes Romeo as "day in night" and "Whiter than snow upon a raven's back." This contrast of light and dark can be expanded as symbols—contrasting love and hate, youth and age in a metaphoric way. Sometimes these intertwining metaphors create

dramatic irony.

For example, Romeo and Juliet's love is a light in the midst of the

darkness of the hate around them, but all of their activity together is

done in night and darkness, while all of the feuding is done in broad

daylight. This paradox of imagery adds atmosphere to the

moral dilemma

facing the two lovers: loyalty to family or loyalty to love. At the end

of the story, when the morning is gloomy and the sun hiding its face

for sorrow, light and dark have returned to their proper places, the

outward darkness reflecting the true, inner darkness of the family feud

out of sorrow for the lovers. All characters now recognise their folly

in light of recent events, and things return to the natural order,

thanks to the love and death of Romeo and Juliet.

The "light" theme in the play is also heavily connected to the theme of

time, since light was a convenient way for Shakespeare to express the

passage of time through descriptions of the sun, moon, and stars.

Time

"These times of woe afford no time to woo."

—Paris, Act III Scene IV

Time plays an important role in the language and plot of the play.

Both Romeo and Juliet struggle to maintain an imaginary world void of

time in the face of the harsh realities that surround them. For

instance, when Romeo swears his love to Juliet by the moon, she protests

"O swear not by the moon, th'inconstant moon, / That monthly changes in

her circled orb, / Lest that thy love prove likewise variable." From the very beginning, the lovers are designated as "star-cross'd" referring to an

astrologic

belief associated with time. Stars were thought to control the fates of

humanity, and as time passed, stars would move along their course in

the sky, also charting the course of human lives below. Romeo speaks of a

foreboding he feels in the stars' movements early in the play, and when

he learns of Juliet's death, he defies the stars' course for him.

Another central theme is haste: Shakespeare's

Romeo and Juliet spans a period of four to six days, in contrast to Brooke's poem's spanning nine months.

Scholars such as G. Thomas Tanselle believe that time was "especially

important to Shakespeare" in this play, as he used references to

"short-time" for the young lovers as opposed to references to

"long-time" for the "older generation" to highlight "a headlong rush

towards doom".

Romeo and Juliet fight time to make their love last forever. In the

end, the only way they seem to defeat time is through a death that makes

them immortal through art.

Time is also connected to the theme of light and dark. In

Shakespeare's day, plays were most often performed at noon or in the

afternoon in broad daylight.

This forced the playwright to use words to create the illusion of day

and night in his plays. Shakespeare uses references to the night and

day, the stars, the moon, and the sun to create this illusion. He also

has characters frequently refer to days of the week and specific hours

to help the audience understand that time has passed in the story. All

in all, no fewer than 103 references to time are found in the play,

adding to the illusion of its passage.

Criticism and interpretation

Critical history

The earliest known critic of the play was diarist

Samuel Pepys, who wrote in 1662: "it is a play of itself the worst that I ever heard in my life." Poet

John Dryden wrote 10 years later in praise of the play and its comic character Mercutio: "Shakespear show'd the best of his skill in his

Mercutio, and he said himself, that he was forc'd to kill him in the third Act, to prevent being killed by him." Criticism of the play in the 18th century was less sparse, but no less divided. Publisher

Nicholas Rowe

was the first critic to ponder the theme of the play, which he saw as

the just punishment of the two feuding families. In mid-century, writer

Charles Gildon and philosopher

Lord Kames

argued that the play was a failure in that it did not follow the

classical rules of drama: the tragedy must occur because of some

character flaw, not an accident of fate. Writer and critic

Samuel Johnson, however, considered it one of Shakespeare's "most pleasing" plays.

In the later part of the 18th and through the 19th century, criticism

centred on debates over the moral message of the play. Actor and

playwright

David Garrick's 1748 adaptation excluded Rosaline: Romeo abandoning her for Juliet was seen as fickle and reckless. Critics such as

Charles Dibdin

argued that Rosaline had been purposely included in the play to show

how reckless the hero was, and that this was the reason for his tragic

end. Others argued that Friar Laurence might be Shakespeare's spokesman

in his warnings against undue haste. With the advent of the 20th

century, these moral arguments were disputed by critics such as

Richard Green Moulton: he argued that accident, and not some character flaw, led to the lovers' deaths.

Dramatic structure

In

Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare employs several dramatic

techniques that have garnered praise from critics; most notably the

abrupt shifts from comedy to tragedy (an example is the

punning

exchange between Benvolio and Mercutio just before Tybalt arrives).

Before Mercutio's death in Act three, the play is largely a comedy.

After his accidental demise, the play suddenly becomes serious and

takes on a tragic tone. When Romeo is banished, rather than executed,

and Friar Laurence offers Juliet a plan to reunite her with Romeo, the

audience can still hope that all will end well. They are in a

"breathless state of suspense" by the opening of the last scene in the

tomb: If Romeo is delayed long enough for the Friar to arrive, he and

Juliet may yet be saved.

These shifts from hope to despair, reprieve, and new hope, serve to

emphasise the tragedy when the final hope fails and both the lovers die

at the end.

Shakespeare also uses sub-plots to offer a clearer view of the

actions of the main characters. For example, when the play begins, Romeo

is in love with Rosaline, who has refused all of his advances. Romeo's

infatuation with her stands in obvious contrast to his later love for

Juliet. This provides a comparison through which the audience can see

the seriousness of Romeo and Juliet's love and marriage. Paris' love for

Juliet also sets up a contrast between Juliet's feelings for him and

her feelings for Romeo. The formal language she uses around Paris, as

well as the way she talks about him to her Nurse, show that her feelings

clearly lie with Romeo. Beyond this, the

sub-plot

of the Montague–Capulet feud overarches the whole play, providing an

atmosphere of hate that is the main contributor to the play's tragic

end.

Language

Shakespeare uses a variety of poetic forms throughout the play. He begins with a 14-line

prologue in the form of a

Shakespearean sonnet, spoken by a Chorus. Most of

Romeo and Juliet is, however, written in

blank verse, and much of it in strict

iambic pentameter, with less rhythmic variation than in most of Shakespeare's later plays. In choosing forms, Shakespeare matches the poetry to the character who uses it. Friar Laurence, for example, uses

sermon and

sententiae forms, and the Nurse uses a unique

blank verse form that closely matches

colloquial speech.

Each of these forms is also moulded and matched to the emotion of the

scene the character occupies. For example, when Romeo talks about

Rosaline earlier in the play, he attempts to use the

Petrarchan sonnet

form. Petrarchan sonnets were often used by men to exaggerate the

beauty of women who were impossible for them to attain, as in Romeo's

situation with Rosaline. This sonnet form is used by Lady Capulet to

describe Count Paris to Juliet as a handsome man.

When Romeo and Juliet meet, the poetic form changes from the Petrarchan

(which was becoming archaic in Shakespeare's day) to a then more

contemporary sonnet form, using "pilgrims" and "saints" as metaphors.

Finally, when the two meet on the balcony, Romeo attempts to use the

sonnet form to pledge his love, but Juliet breaks it by saying "Dost

thou love me?" By doing this, she searches for true expression, rather than a poetic exaggeration of their love. Juliet uses monosyllabic words with Romeo, but uses formal language with Paris. Other forms in the play include an

epithalamium by Juliet, a

rhapsody in Mercutio's

Queen Mab speech, and an

elegy by Paris.

Shakespeare saves his prose style most often for the common people in

the play, though at times he uses it for other characters, such as

Mercutio. Humour, also, is important: scholar Molly Mahood identifies at least 175 puns and wordplays in the text. Many of these jokes are sexual in nature, especially those involving Mercutio and the Nurse.

Psychoanalytic criticism

Early

psychoanalytic critics saw the problem of

Romeo and Juliet

in terms of Romeo's impulsiveness, deriving from "ill-controlled,

partially disguised aggression", which leads both to Mercutio's death

and to the double suicide.

Romeo and Juliet

is not considered to be exceedingly psychologically complex, and

sympathetic psychoanalytic readings of the play make the tragic male

experience equivalent with sicknesses. Norman Holland, writing in 1966, considers Romeo's dream

as a realistic "wish fulfilling fantasy both in terms of Romeo's adult

world and his hypothetical childhood at stages oral, phallic and

oedipal" – while acknowledging that a dramatic character is not a human

being with mental processes separate from those of the author. Critics such as

Julia Kristeva

focus on the hatred between the families, arguing that this hatred is

the cause of Romeo and Juliet's passion for each other. That hatred

manifests itself directly in the lovers' language: Juliet, for example,

speaks of "my only love sprung from my only hate" and often expresses her passion through an anticipation of Romeo's death.

This leads on to speculation as to the playwright's psychology, in

particular to a consideration of Shakespeare's grief for the death of

his son,

Hamnet.

Feminist criticism

Feminist literary critics argue that the blame for the family feud lies in Verona's

patriarchal society.

For Coppélia Kahn, for example, the strict, masculine code of violence

imposed on Romeo is the main force driving the tragedy to its end. When

Tybalt kills Mercutio, Romeo shifts into this violent mode, regretting

that Juliet has made him so "effeminate".

In this view, the younger males "become men" by engaging in violence on

behalf of their fathers, or in the case of the servants, their masters.

The feud is also linked to male virility, as the numerous jokes about

maidenheads aptly demonstrate.

Juliet also submits to a female code of docility by allowing others,

such as the Friar, to solve her problems for her. Other critics, such as

Dympna Callaghan, look at the play's feminism from a

historicist

angle, stressing that when the play was written the feudal order was

being challenged by increasingly centralised government and the advent

of capitalism. At the same time, emerging

Puritan

ideas about marriage were less concerned with the "evils of female

sexuality" than those of earlier eras, and more sympathetic towards

love-matches: when Juliet dodges her father's attempt to force her to

marry a man she has no feeling for, she is challenging the patriarchal

order in a way that would not have been possible at an earlier time.

Queer theory

A number of critics have found the character of Mercutio to have unacknowledged homoerotic desire for Romeo. Jonathan Goldberg examined the sexuality of Mercutio and Romeo utilising "

queer theory" in

Queering the Renaissance, comparing their friendship with sexual love. Mercutio, in friendly conversation, mentions Romeo's

phallus, suggesting traces of

homoeroticism.

An example is his joking wish "To raise a spirit in his mistress'

circle ... letting it there stand / Till she had laid it and conjured it

down."

Romeo's homoeroticism can also be found in his attitude to Rosaline, a

woman who is distant and unavailable and brings no hope of offspring. As

Benvolio argues, she is best replaced by someone who will reciprocate.

Shakespeare's

procreation sonnets

describe another young man who, like Romeo, is having trouble creating

offspring and who may be seen as being a homosexual. Goldberg believes

that Shakespeare may have used Rosaline as a way to express homosexual

problems of procreation in an acceptable way. In this view, when Juliet

says "...that which we call a rose, by any other name would smell as

sweet", she may be raising the question of whether there is any difference between the beauty of a man and the beauty of a woman.

The Balcony Scene

The balcony scene was introduced by Da Porto in 1524. He had Romeo

walk frequently by her house, "sometimes climbing to her chamber window"

and wrote "It happened one night, as love ordained, when the moon shone

unusually bright, that whilst Romeo was climbing the balcony, the young

lady ... opened the window, and looking out saw him".

After this they have a conversation in which they declare eternal love

to each other. A few decades later, Bandello greatly expanded this

scene, diverging from the familiar one: Julia has her nurse deliver a

letter asking Romeo to come to her window with a rope ladder, and he

climbs the balcony with the help of his servant, Julia and the nurse

(the servants discreetly withdraw after this).

Nevertheless, in October 2014, Lois Leveen speculated in

The Atlantic that the original Shakespeare play did not contain a balcony. The word,

balcone, did not exist in the English language until two years after Shakespeare's death.

The balcony was certainly used in

Thomas Otway's 1679 play,

The History and Fall of Caius Marius, which had borrowed much of its story from

Romeo and Juliet

and placed the two lovers in a balcony reciting a speech similar to

that between Romeo and Juliet. Leveen suggested that during the 18th

century,

David Garrick chose to use a balcony in his adaptation and revival of

Romeo and Juliet and modern adaptations have continued this tradition.

Legacy

Shakespeare's day

Romeo and Juliet ranks with

Hamlet as one of Shakespeare's most performed plays. Its many adaptations have made it one of his most enduring and famous stories.

Even in Shakespeare's lifetime it was extremely popular. Scholar Gary

Taylor measures it as the sixth most popular of Shakespeare's plays, in

the period after the death of

Christopher Marlowe and

Thomas Kyd but before the ascendancy of

Ben Jonson during which Shakespeare was London's dominant playwright.

The date of the first performance is unknown. The First Quarto, printed

in 1597, says that "it hath been often (and with great applause) plaid

publiquely", setting the first performance before that date. The

Lord Chamberlain's Men were certainly the first to perform it. Besides their strong connections with Shakespeare, the

Second Quarto actually names one of its actors,

Will Kemp, instead of Peter in a line in Act five.

Richard Burbage was probably the first Romeo, being the company's actor, and Master Robert Goffe (a boy) the first Juliet. The premiere is likely to have been at "

The Theatre", with other early productions at "

The Curtain".

Romeo and Juliet

is one of the first Shakespearean plays to have been performed outside

England: a shortened and simplified version was performed in

Nördlingen in 1604.

Restoration and 18th-century theatre

All theatres were closed down by the

puritan government on September 6, 1642. Upon the

restoration of the monarchy in 1660, two patent companies (the

King's Company and the

Duke's Company) were established, and the existing theatrical repertoire divided between them.

Sir

William Davenant of the Duke's Company staged a 1662 adaptation in which

Henry Harris played Romeo,

Thomas Betterton Mercutio, and Betterton's wife

Mary Saunderson Juliet: she was probably the first woman to play the role professionally.

Another version closely followed Davenant's adaptation and was also

regularly performed by the Duke's Company. This was a tragicomedy by

James Howard, in which the two lovers survive.

Thomas Otway's

The History and Fall of Caius Marius,

one of the more extreme of the Restoration adaptations of Shakespeare,

debuted in 1680. The scene is shifted from Renaissance Verona to

ancient Rome;

Romeo is Marius, Juliet is Lavinia, the feud is between patricians and

plebeians; Juliet/Lavinia wakes from her potion before Romeo/Marius

dies. Otway's version was a hit, and was acted for the next seventy

years. His innovation in the closing scene was even more enduring, and was used in adaptations throughout the next 200 years:

Theophilus Cibber's adaptation of 1744, and

David Garrick's of 1748 both used variations on it. These versions also eliminated elements deemed inappropriate at the

time. For example, Garrick's version transferred all language describing

Rosaline to Juliet, to heighten the idea of faithfulness and downplay

the love-at-first-sight theme. In 1750 a "Battle of the Romeos" began, with

Spranger Barry and

Susannah Maria Arne (Mrs. Theophilus Cibber) at

Covent Garden versus

David Garrick and

George Anne Bellamy at

Drury Lane.

The earliest known production in North America was an amateur one: on

23 March 1730, a physician named Joachimus Bertrand placed an

advertisement in the

Gazette newspaper in New York, promoting a production in which he would play the apothecary. The first professional performances of the play in North America were those of the

Hallam Company.

19th-century theatre

The American Cushman sisters,

Charlotte and

Susan, as Romeo and Juliet in 1846

Garrick's altered version of the play was very popular, and ran for nearly a century. Not until 1845 did Shakespeare's original return to the stage in the United States with the sisters

Susan and

Charlotte Cushman as Juliet and Romeo, respectively, and then in 1847 in Britain with

Samuel Phelps at

Sadler's Wells Theatre.

Cushman adhered to Shakespeare's version, beginning a string of

eighty-four performances. Her portrayal of Romeo was considered genius

by many.

The Times

wrote: "For a long time Romeo has been a convention. Miss Cushman's

Romeo is a creative, a living, breathing, animated, ardent human being."

Queen Victoria wrote in her journal that "no-one would ever have imagined she was a woman".

Cushman's success broke the Garrick tradition and paved the way for later performances to return to the original storyline.

Professional performances of Shakespeare in the mid-19th century had two particular features: firstly, they were generally

star vehicles,

with supporting roles cut or marginalised to give greater prominence to

the central characters. Secondly, they were "pictorial", placing the

action on spectacular and elaborate sets (requiring lengthy pauses for

scene changes) and with the frequent use of

tableaux.

Henry Irving's 1882 production at the

Lyceum Theatre (with himself as Romeo and

Ellen Terry as Juliet) is considered an archetype of the pictorial style. In 1895, Sir

Johnston Forbes-Robertson

took over from Irving, and laid the groundwork for a more natural

portrayal of Shakespeare that remains popular today. Forbes-Robertson

avoided the showiness of Irving and instead portrayed a down-to-earth

Romeo, expressing the poetic dialogue as realistic prose and avoiding

melodramatic flourish.

American actors began to rival their British counterparts.

Edwin Booth (brother to

John Wilkes Booth) and Mary McVicker (soon to be Edwin's wife) opened as Romeo and Juliet at the sumptuous

Booth's Theatre (with its European-style

stage machinery,

and an air conditioning system unique in New York) on 3 February 1869.

Some reports said it was one of the most elaborate productions of

Romeo and Juliet ever seen in America; it was certainly the most popular, running for over six weeks and earning over $60,000 (equal to about $1,067,000 today).

The programme noted that: "The tragedy will be produced in strict

accordance with historical propriety, in every respect, following

closely the text of Shakespeare."

The first professional performance of the play in Japan may have been

George Crichton Miln's company's production, which toured to

Yokohama in 1890. Throughout the 19th century,

Romeo and Juliet

had been Shakespeare's most popular play, measured by the number of

professional performances. In the 20th century it would become the

second most popular, behind

Hamlet.

20th-century theatre

In 1933, the play was revived by actress

Katharine Cornell and her director husband

Guthrie McClintic and was taken on a seven-month nationwide tour throughout the United States. It starred

Orson Welles,

Brian Aherne and

Basil Rathbone.

The production was a modest success, and so upon the return to New

York, Cornell and McClintic revised it and for the first time, the play

was presented with almost all the scenes intact, including the Prologue.

The new production opened in December 1934 with

Ralph Richardson as Mercutio and

Maurice Evans

as Romeo. Critics wrote that Cornell was "the finest Juliet of her

time", "endlessly haunting", and "the most lovely and enchanting Juliet

our present-day theatre has seen".

John Gielgud, who was among the more famous 20th-century actors to play Romeo, Friar Laurence and Mercutio on stage

John Gielgud's

New Theatre production in 1935 featured Gielgud and

Laurence Olivier as Romeo and Mercutio, exchanging roles six weeks into the run, with

Peggy Ashcroft as Juliet.

Gielgud used a scholarly combination of Q1 and Q2 texts, and organised

the set and costumes to match as closely as possible to the

Elizabethan period. His efforts were a huge success at the box office, and set the stage for increased

historical realism in later productions.

Olivier later compared his performance and Gielgud's: "John, all

spiritual, all spirituality, all beauty, all abstract things; and myself

as all earth, blood, humanity ... I've always felt that John missed the

lower half and that made me go for the other ... But whatever it was,

when I was playing Romeo I was carrying a torch, I was trying to sell

realism in Shakespeare."

Peter Brook's 1947 version was the beginning of a different style of

Romeo and Juliet

performances. Brook was less concerned with realism, and more concerned

with translating the play into a form that could communicate with the

modern world. He argued, "A production is only correct at the moment of

its correctness, and only good at the moment of its success." Brook excluded the final reconciliation of the families from his performance text.

Throughout the century, audiences, influenced by the cinema, became

less willing to accept actors distinctly older than the teenage

characters they were playing. A significant example of more youthful casting was in

Franco Zeffirelli's

Old Vic production in 1960, with

John Stride and

Judi Dench, which would serve as the basis for his

1968 film.

Zeffirelli borrowed from Brook's ideas, altogether removing around a

third of the play's text to make it more accessible. In an interview

with

The Times, he stated that the play's "twin themes of love

and the total breakdown of understanding between two generations" had

contemporary relevance.

Recent performances often set the play in the contemporary world. For example, in 1986 the

Royal Shakespeare Company set the play in modern

Verona. Switchblades replaced swords, feasts and balls became drug-laden rock parties, and Romeo committed suicide by

hypodermic needle. In 1997, the

Folger Shakespeare Theatre

produced a version set in a typical suburban world. Romeo sneaks into

the Capulet barbecue to meet Juliet, and Juliet discovers Tybalt's death

while in class at school.

The play is sometimes given a historical setting, enabling audiences

to reflect on the underlying conflicts. For example, adaptations have

been set in the midst of the

Israeli-Palestinian conflict, in the

apartheid era in South Africa, and in the aftermath of the

Pueblo Revolt. Similarly,

Peter Ustinov's 1956 comic adaptation,

Romanoff and Juliet, is set in a fictional mid-European country in the depths of the

Cold War. A mock-Victorian revisionist version of

Romeo and Juliet's

final scene (with a happy ending, Romeo, Juliet, Mercutio and Paris

restored to life, and Benvolio revealing that he is Paris's love,

Benvolia, in disguise) forms part of the 1980 stage-play

The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby.

Shakespeare’s R&J, by Joe Calarco, spins the classic in a modern tale of gay teenage awakening. A recent comedic musical adaptation was

The Second City's

The Second City's Romeo and Juliet Musical: The People vs. Friar Laurence, the Man Who Killed Romeo and Juliet, set in modern times.

In the 19th and 20th century,

Romeo and Juliet has often been the choice of Shakespeare plays to open a classical theatre company, beginning with

Edwin Booth's inaugural production of that play in his theatre in 1869, the newly reformed company of the

Old Vic in 1929 with

John Gielgud,

Martita Hunt and

Margaret Webster, as well as the

Riverside Shakespeare Company in its founding production in New York City in 1977, which used the 1968 film of

Franco Zeffirelli's production as its inspiration.

In 2013,

Romeo and Juliet ran on Broadway at

Richard Rodgers Theatre from September 19 to December 8 for 93 regular performances after 27 previews starting on August 24 with

Orlando Bloom and

Condola Rashad in the starring roles.

Ballet

The best-known ballet version is

Prokofiev's

Romeo and Juliet. Originally commissioned by the

Kirov Ballet,

it was rejected by them when Prokofiev attempted a happy ending, and

was rejected again for the experimental nature of its music. It has

subsequently attained an "immense" reputation, and has been

choreographed by

John Cranko (1962) and

Kenneth MacMillan (1965) among others.

In 1977,

Michael Smuin's production of one of the play's most dramatic and impassioned dance interpretations was debuted in its entirety by

San Francisco Ballet. This production was the first full-length ballet to be broadcast by the

PBS series "

Great Performances: Dance in America"; it aired in 1978.

Music

"Romeo loved Juliet

Juliet, she felt the same

When he put his arms around her

He said Julie, baby, you're my flame

Thou givest fever ..."

—Peggy Lee's rendition of "Fever".

At least 27 operas have been based on Romeo and Juliet. The earliest,

Romeo und Julie in 1776, a

Singspiel by

Georg Benda,

omits much of the action of the play and most of its characters, and

has a happy ending. It is occasionally revived. The best-known is

Gounod's 1867

Roméo et Juliette (libretto by

Jules Barbier and

Michel Carré), a critical triumph when first performed and frequently revived today.

Bellini's I Capuleti e i Montecchi

is also revived from time to time, but has sometimes been judged

unfavourably because of its perceived liberties with Shakespeare;

however, Bellini and his librettist,

Felice Romani, worked from Italian sources—principally Romani's libretto for

Giulietta e Romeo by

Nicola Vaccai—rather than directly adapting Shakespeare's play. Among later operas there is

Heinrich Sutermeister's 1940 work

Romeo und Julia.

Roméo et Juliette by

Berlioz is a "symphonie dramatique", a large-scale work in three parts for mixed voices, chorus and orchestra, which premiered in 1839.

Tchaikovsky's

Romeo and Juliet Fantasy-Overture (1869, revised 1870 and 1880) is a 15-minute

symphonic poem, containing the famous melody known as the "love theme". Tchaikovsky's device of repeating the same musical theme at the ball, in the balcony scene, in Juliet's bedroom and in the tomb has been used by subsequent directors: for example

Nino Rota's love theme is used in a similar way in the 1968 film of the play, as is

Des'ree's

Kissing You in the 1996 film. Other classical composers influenced by the play include

Henry Hugh Pearson (

Romeo and Juliet, overture for orchestra, Op. 86),

Svendsen (

Romeo og Julie, 1876),

Delius (

A Village Romeo and Juliet, 1899–1901),

Stenhammar (

Romeo och Julia, 1922), and

Kabalevsky (

Incidental Music to Romeo and Juliet, Op. 56, 1956).

The play influenced several

jazz works, including

Peggy Lee's "

Fever".

Duke Ellington's

Such Sweet Thunder contains a piece entitled "The Star-Crossed Lovers"

in which the pair are represented by tenor and alto saxophones: critics

noted that Juliet's sax dominates the piece, rather than offering an

image of equality. The play has frequently influenced

popular music, including works by

The Supremes,

Bruce Springsteen,

Tom Waits,

Lou Reed, and

Taylor Swift. The most famous such track is

Dire Straits' "

Romeo and Juliet".

The most famous musical theatre adaptation is

West Side Story with music by

Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by

Stephen Sondheim.

It débuted on Broadway in 1957 and in the West End in 1958, and became a

popular film in 1961. This version updated the setting to

mid-20th-century New York City, and the warring families to ethnic

gangs. Other musical adaptations include

Terrence Mann's 1999 rock musical

William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, co-written with Jerome Korman,

[163] Gérard Presgurvic's 2001

Roméo et Juliette, de la Haine à l'Amour and

Riccardo Cocciante's 2007

Giulietta & Romeo.

Literature and art

Romeo and Juliet had a profound influence on subsequent literature. Before then, romance had not even been viewed as a worthy topic for tragedy.

In Harold Bloom's words, Shakespeare "invented the formula that the

sexual becomes the erotic when crossed by the shadow of death".

Of Shakespeare's works,

Romeo and Juliet

has generated the most—and the most varied—adaptations, including prose

and verse narratives, drama, opera, orchestral and choral music,

ballet, film, television and painting. The word "Romeo" has even become synonymous with "male lover" in English.

Romeo and Juliet was parodied in Shakespeare's own lifetime:

Henry Porter's

Two Angry Women of Abingdon (1598) and

Thomas Dekker's

Blurt, Master Constable (1607) both contain balcony scenes in which a virginal heroine engages in bawdy wordplay. The play directly influenced later

literary works. For example, the preparations for a performance form a major plot arc in

Charles Dickens'

Nicholas Nickleby.

Romeo and Juliet is one of Shakespeare's most-illustrated works. The first known illustration was a woodcut of the tomb scene,thought to be by Elisha Kirkall, which appeared in

Nicholas Rowe's 1709 edition of Shakespeare's plays. Five paintings of the play were commissioned for the

Boydell Shakespeare Gallery in the late 18th century, one representing each of the five acts of the play.

The 19th century fashion for "pictorial" performances led to directors

drawing on paintings for their inspiration, which in turn influenced

painters to depict actors and scenes from the theatre. In the 20th century, the play's most iconic visual images have derived from its popular film versions.

In 2014, Simon & Schuster will publish

Juliet's Nurse, a novel by historian and former college professor

Lois M. Leveen

imagining the fourteen years leading up to the events in the play from

the point of view of the nurse. The nurse has the third largest number

of lines in the original play; only the eponymous characters have more

lines.

Screen

Romeo and Juliet may be the most-filmed play of all time. The most notable theatrical releases were

George Cukor's multi-

Oscar-nominated

1936 production,

Franco Zeffirelli's

1968 version, and

Baz Luhrmann's 1996 MTV-inspired

Romeo + Juliet. The latter two were both, in their time, the highest-grossing Shakespeare film ever.

Romeo and Juliet was first filmed in the silent era, by

Georges Méliès, although his film is now lost. The play was first heard on film in

The Hollywood Revue of 1929, in which

John Gilbert recited the balcony scene opposite

Norma Shearer.

Leslie Howard as Romeo and Norma Shearer as Juliet, in the 1936 MGM film directed by

George Cukor.

Shearer and

Leslie Howard, with a combined age over 75, played the teenage lovers in

George Cukor's

MGM 1936 film version.

Neither critics nor the public responded enthusiastically. Cinemagoers

considered the film too "arty", staying away as they had from Warner's

A Midsummer Night Dream a year before: leading to Hollywood abandoning the Bard for over a decade.

Renato Castellani won the

Grand Prix at the

Venice Film Festival for his

1954 film of Romeo and Juliet. His Romeo,

Laurence Harvey, was already an experienced screen actor.

By contrast, Susan Shentall, as Juliet, was a secretarial student who

was discovered by the director in a London pub, and was cast for her

"pale sweet skin and honey-blonde hair".

Stephen Orgel describes

Franco Zeffirelli's

1968 Romeo and Juliet

as being "full of beautiful young people, and the camera, and the lush

technicolour, make the most of their sexual energy and good looks".

Zeffirelli's teenage leads,

Leonard Whiting and

Olivia Hussey, had virtually no previous acting experience, but performed capably and with great maturity. Zeffirelli has been particularly praised, for his presentation of the duel scene as bravado getting out-of-control. The film courted controversy by including a nude wedding-night scene while Olivia Hussey was only fifteen.

Baz Luhrmann's 1996

Romeo + Juliet and its

accompanying soundtrack successfully targeted the "

MTV Generation": a young audience of similar age to the story's characters.

Far darker than Zeffirelli's version, the film is set in the "crass,

violent and superficial society" of Verona Beach and Sycamore Grove.

Leonardo DiCaprio was Romeo and

Claire Danes was Juliet.

The play has been widely adapted for TV and film. In 1960,

Peter Ustinov's

cold-war stage parody,

Romanoff and Juliet was filmed.

The 1961 film of

West Side Story—set

among New York gangs–featured the Jets as white youths, equivalent to

Shakespeare's Montagues, while the Sharks, equivalent to the Capulets,

are Puerto Rican. The 1994 film

The Punk uses both the rough plot outline of

Romeo and Juliet and names many of the characters in ways that reflect the characters in the play. In 2006, Disney's

High School Musical made use of

Romeo and Juliet's plot, placing the two young lovers in rival high school cliques instead of feuding families. Film-makers have frequently featured characters performing scenes from

Romeo and Juliet. The

conceit of dramatising Shakespeare writing

Romeo and Juliet has been used several times, including

John Madden's 1998

Shakespeare in Love, in which Shakespeare writes the play against the backdrop of his own doomed love affair. An

anime series produced by

Gonzo and

SKY Perfect Well Think, called

Romeo x Juliet, was made in 2007 and the

2013 version is the latest English-language film based on the play. In 2013,

Sanjay Leela Bhansali directed the Bollywood film

Goliyon Ki Raasleela Ram-Leela, a contemporary version of the play which starred

Ranveer Singh and

Deepika Padukone in leading roles. The film was a commercial and critical success. In February 2014,

BroadwayHD released a filmed version of the

2013 Broadway Revival of

Romeo and Juliet. The production starred

Orlando Bloom and

Condola Rashad.

[201] The film was released internationally in April 2014.

Modern social media and virtual world productions

In April and May 2010 the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Mudlark

Production Company presented a version of the play, entitled

Such Tweet Sorrow,

as an improvised, real-time series of tweets on Twitter. The production

used RSC actors who engaged with the audience as well each other,

performing not from a traditional script but a "Grid" developed by the

Mudlark production team and writers Tim Wright and Bethan Marlow. The

performers also make use of other media sites such as YouTube for

pictures and video.

Scene by scene

-

Title page of the

Second Quarto of

Romeo and Juliet published in 1599

-

-

Act I scene 1: Quarrel between Capulets and Montagues

-

-

-

-

-

Act I scene 5: Romeo's first interview with Juliet

-

-

-

Act II scene 5: Juliet intreats her nurse

-

-

Act III scene 5: Romeo takes leave of Juliet

-

Act IV scene 5: Juliet's fake death

-

Act IV scene 5: Another depiction

-

Act V scene 3: Juliet awakes to find Romeo dead